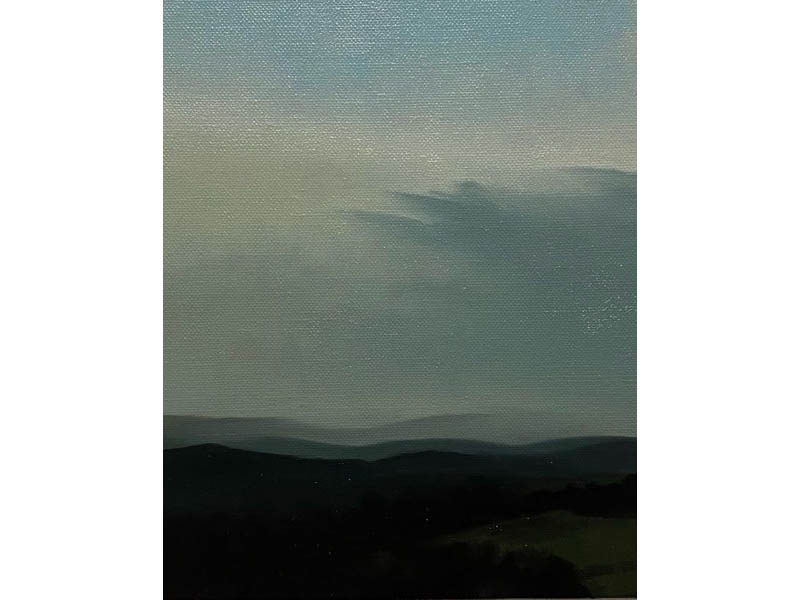

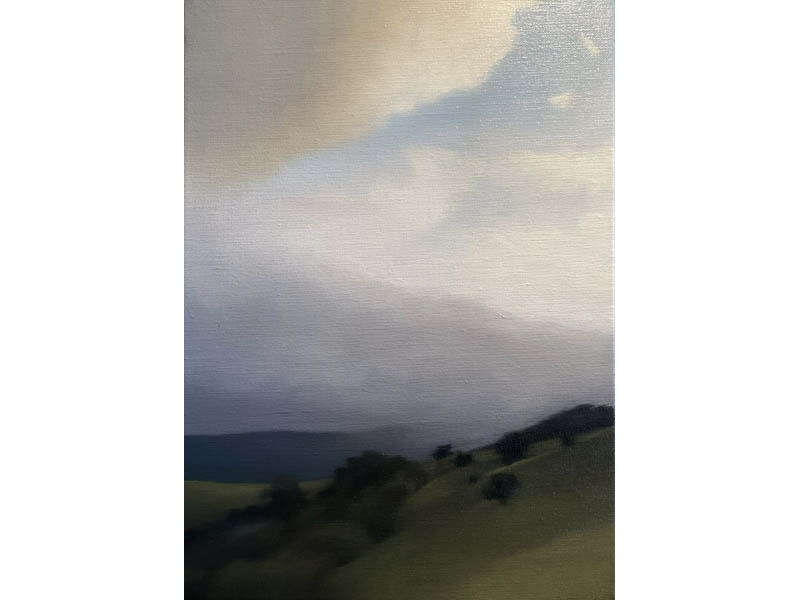

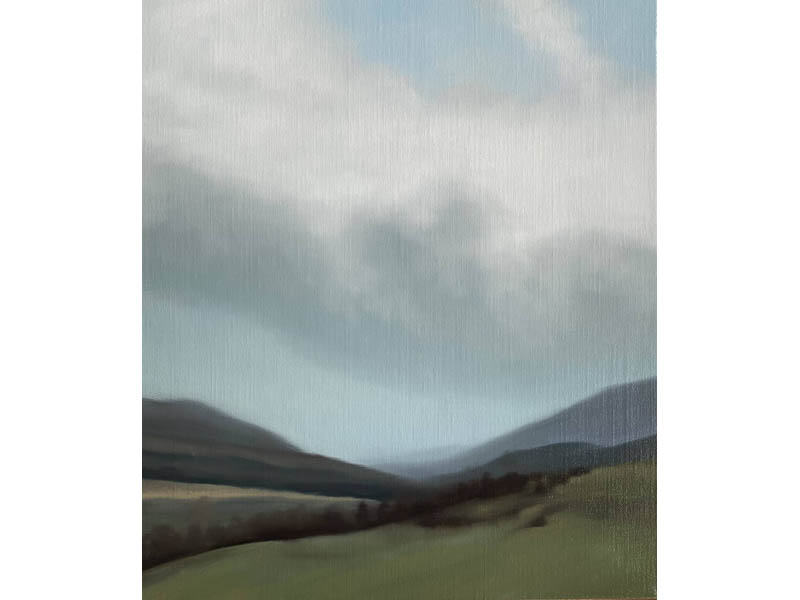

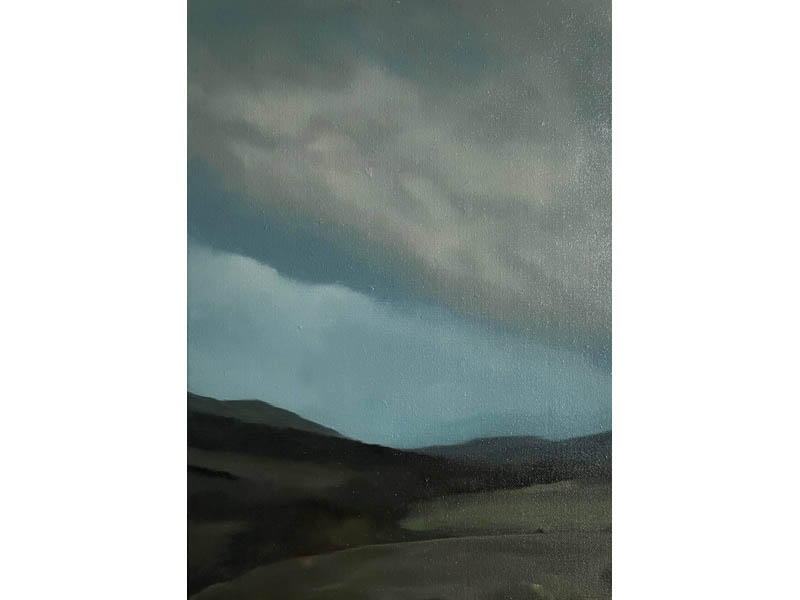

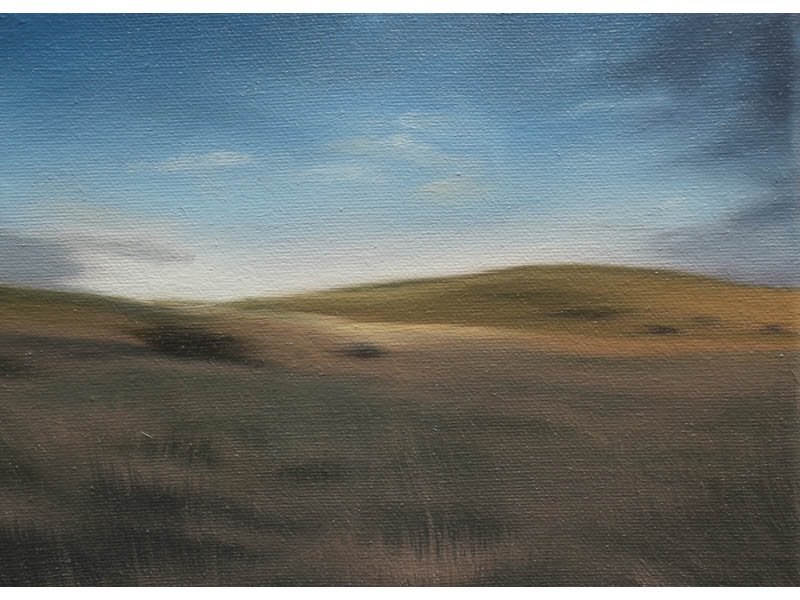

Paul Gundry

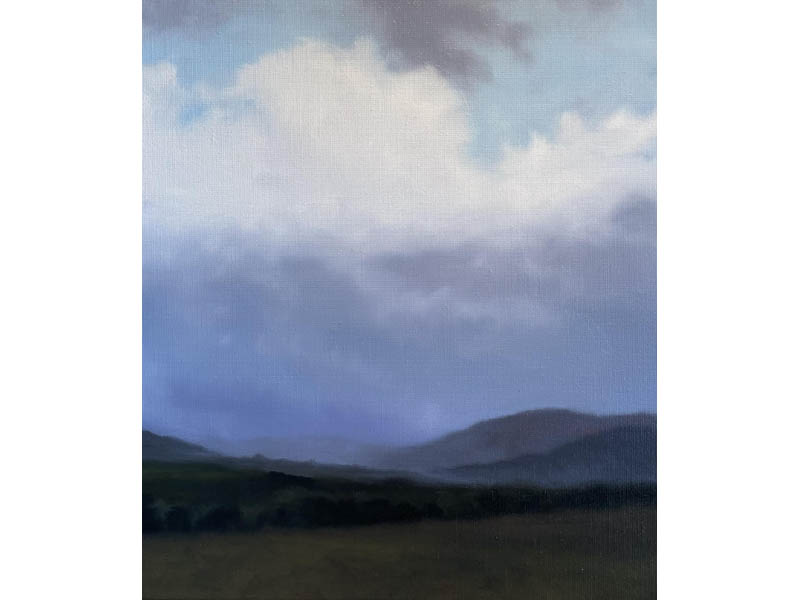

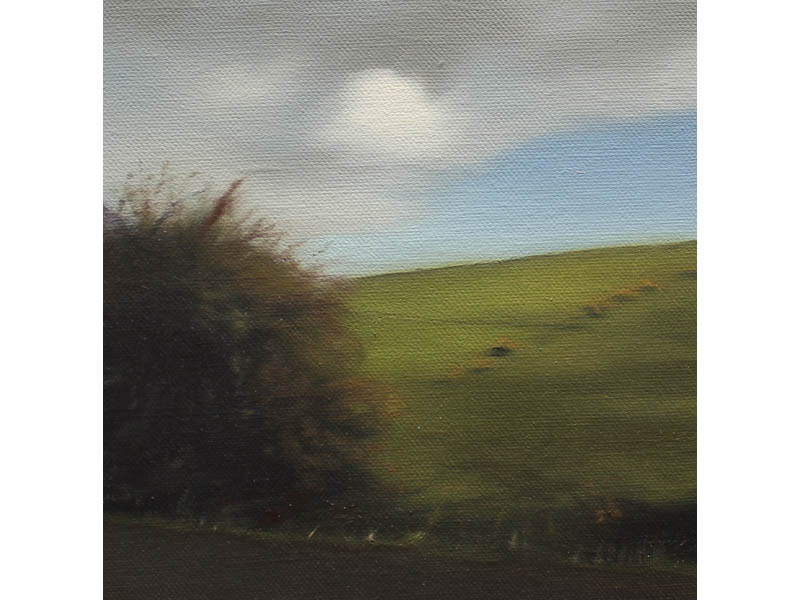

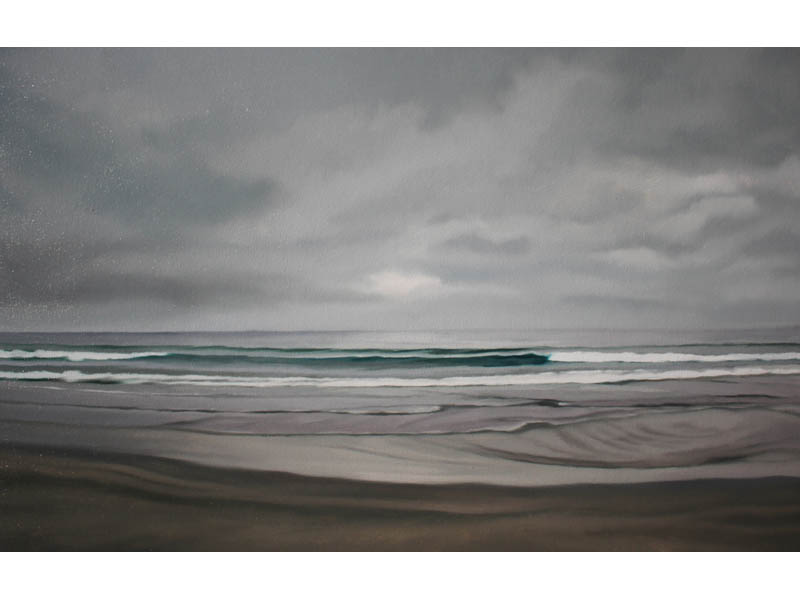

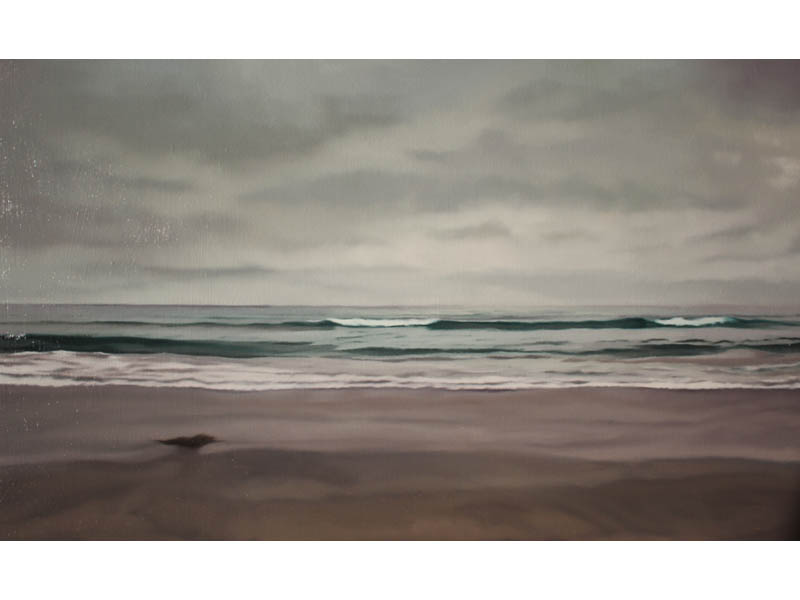

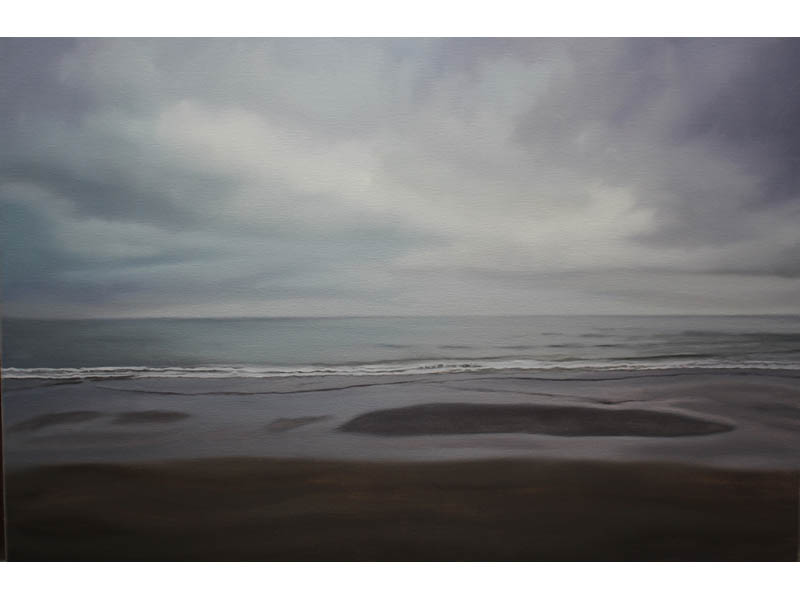

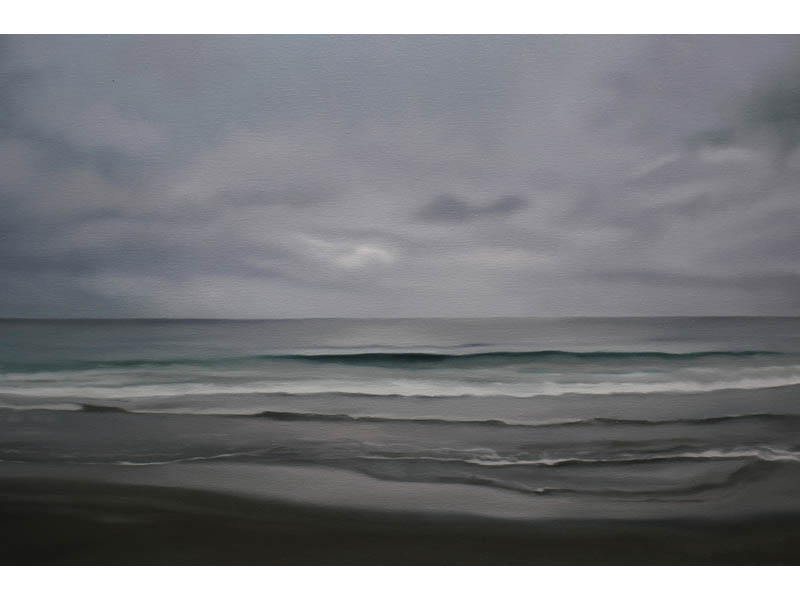

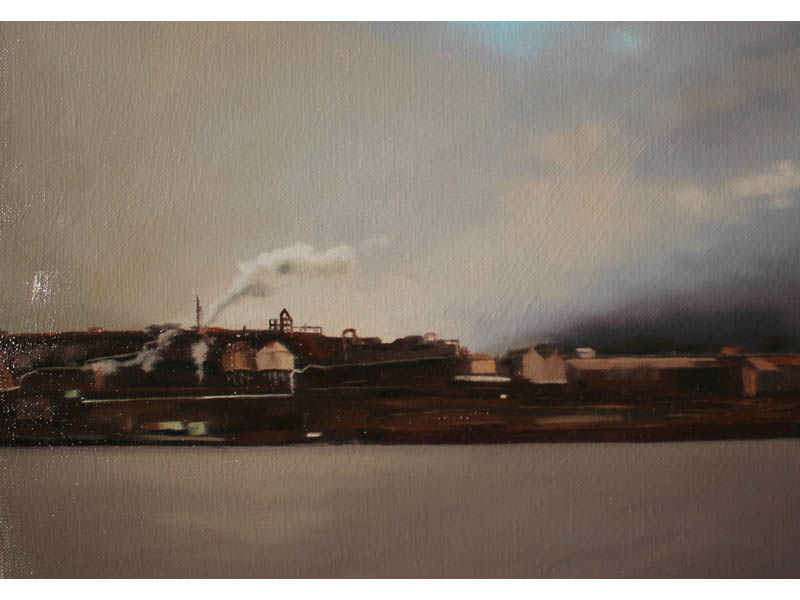

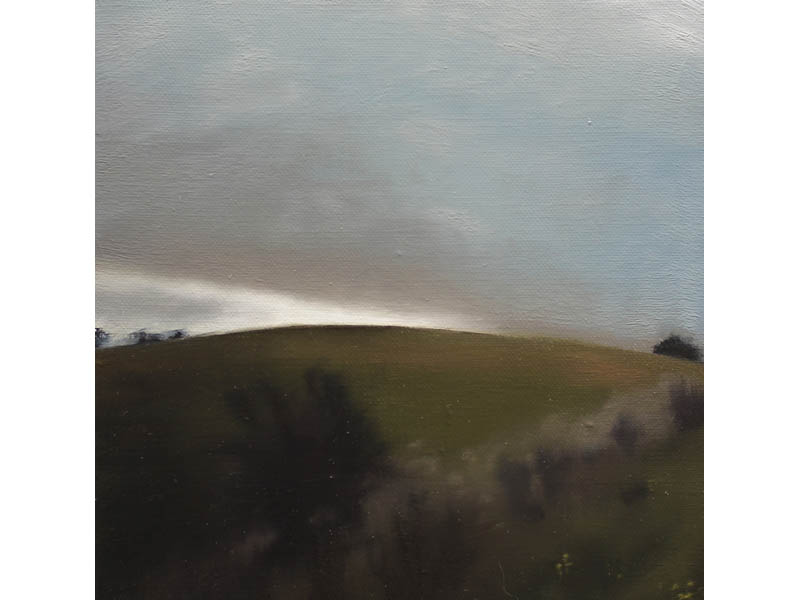

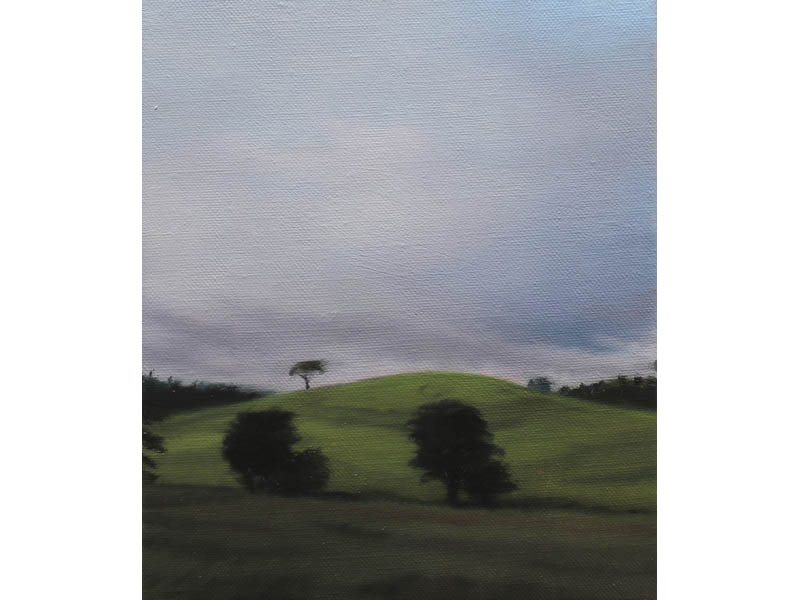

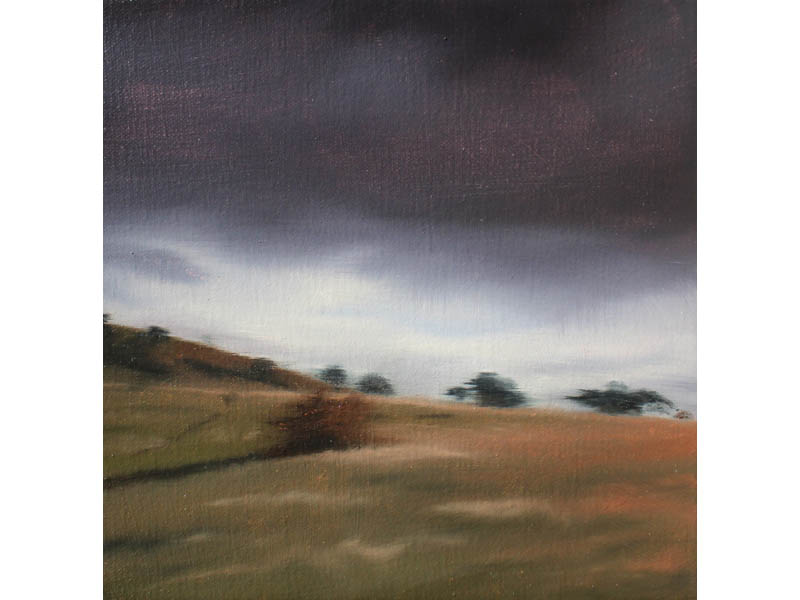

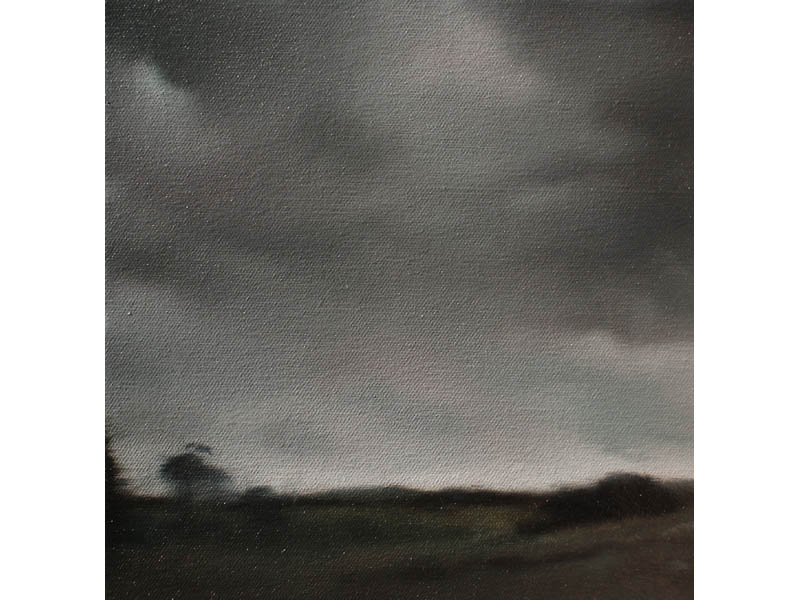

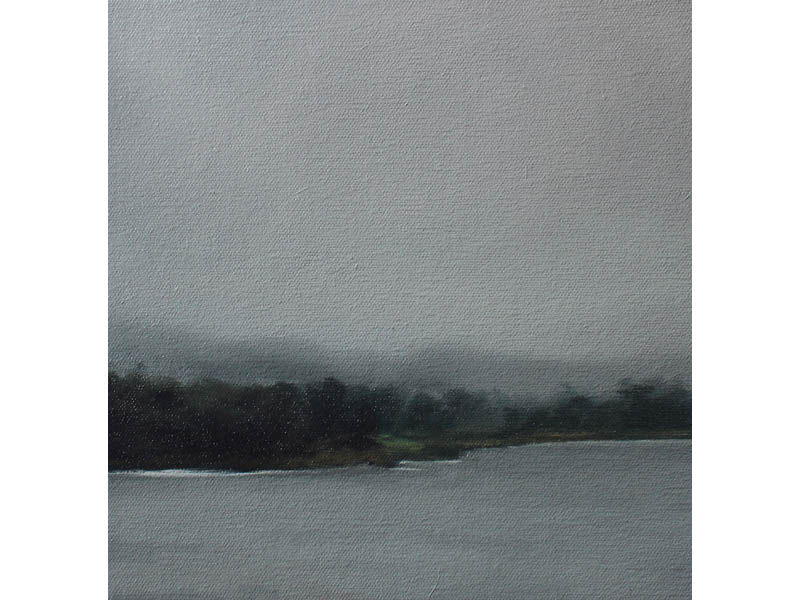

Paul GundryThe theoretical terrain of the ‘eerie’ is well established in the writings of the late Mark Fisher. For Fisher, the eerie concerns the unknown, and the central enigma at its core is the problem of agency: “the sensation of the eerie occurs when there is something present where there should be nothing, or if there is nothing present when there should be something.” The eerie pertains to absences and presences.The eerie has been referred to as, “this scarcely apprehended domain of disquiet” (Charlie Fox). Reflecting on the eerie, Fox contends: “This is what haunts: we are no longer where we thought but somehow trespassing elsewhere and, suddenly, stepping into the otherworldly.” Fisher contended that, “we find the eerie more rapidly in landscapes partially emptied of the human.” Reflecting on the ambient soundscapes of Brian Eno, Fisher speculates that, “there is no doubt a sense of solitude, a withdrawal from the hubbub of banal sociability in On Land but this emerges as a precondition for openness to the outside, where the outside designates, at one level, a radically depastoralized nature, and, at the outer limits, a different, heightened encounter with the real.” Elsewhere, Fisher remarks upon the eerie as it attaches to industrial landscapes, referring to their strange silence: “…the silence is not a physical silence – it’s actually quite noisy. It’s a silence to do with a lack of the sight of human beings. The impression you get when you look at it is of machinery performing its work without the agency of human beings.” Thus, the eerie could be said to pertain to an apprehension of an abstract reality – an experience of disquiet when we sense impersonal, anonymous forces and alien intelligences in the landscape. The eerie is often evoked in association with horror and terror, but Fisher maintained throughout his writings an openness to a more hopeful potential within the experience of the eerie. He remarked that, “what is suppressed in postmodern culture is not the Darkside but the Light side. We are far more comfortable with demons than angels.” He adds, “what could be more shattering than the sensation of calm joy [in contrast with daemonic dread] … far more uncanny in this ultra-agitated present is that mode of the numinous which comes sweeping like a gentle tide, pervading the mind with a tranquil mood of deepest worship.” Fisher rose to his most ardent when writing of those annunciations of the eerie that are not contained or foreclosed within the exclusive domain of abstract horror or ghost story genres – those gesturing to “an outside that – pulsating beyond the confines of the mundane - is achingly alluring even as it is disconcertingly alien.” The extended dimensions of the eerie alluded to in Fisher’s critical writings articulate for me a sense of the eerie as it manifests in the Tasmanian landscape - a landscape that is still dreaming, and full of dreams. |